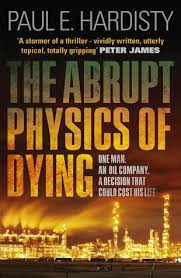

Yemen – PAUL HARDISTY – There’s something fishy going on here…

I am due to meet Paul Hardisty for a chat about his new and debut thriller. We’ve arranged to meet on a dusty beach to recreate the feel of the story in Yemen. He’s also explained that the food he’s bringing instead of our usual cuppa and a cake will require an outside location. What can he mean?

Well, as soon as he appears into view, I know what he means. He’s brought a fish. Freshly caught it seems. Now I understand the need for the beach. Then I notice it’s not cooked – he directs me to a pile of twigs, bringing more and piling them up – then he starts to explain how we’re going to cook this thing. From nowhere he gets out some salt flakes and spices. As it cooks he gets some newspaper from his bag and some flat breads which he places on the sand ready. No washing up he winks.

Well, as soon as he appears into view, I know what he means. He’s brought a fish. Freshly caught it seems. Now I understand the need for the beach. Then I notice it’s not cooked – he directs me to a pile of twigs, bringing more and piling them up – then he starts to explain how we’re going to cook this thing. From nowhere he gets out some salt flakes and spices. As it cooks he gets some newspaper from his bag and some flat breads which he places on the sand ready. No washing up he winks.

What’s for desert? I wonder. Should I have brought a cake? We have eye balls to enjoy he says…..I am not sure what to say to this. I hope its a sweet Yemeni cake of some kind just with a strange name.

Hi Paul! The fish is ready and I’m told to rip it off in pieces like Bear Grylls. The fish is looking at me suspiciously. I fear the Yemeni cake might not happen….

Your background as the Director of Australia’s National Science Agency has certainly given you the insight and the knowledge of your subject. But what made you want to write your debut eco-thriller?

My engineering and science background is a major influence on my writing. The projects I have worked on around the world, and the places that work has taken me, have been a source of inspiration and experience. In the case of The Abrupt Physics of Dying, acts of willful destruction of precious water that the poorest people depend on, sparked the story. The drive to write, however, has always been there. I have published a couple of technical books, dozens of scientific papers. I even wrote an environmental newspaper column for five years for the Cyprus English language daily. But in the background has always been the fiction, accumulated in stacks of notebooks lining my shelves since I was young.

The book is set primarily in Yemen. What kind of research did you do to portray the land and its people?

I worked all over Yemen, from Sana’a and Aden to the Masila and Hadramawt, over a fifteen year period in the eighties and nineties. It was a wild and dangerous place then, still is now. And as I went, I wrote. It’s the kind of place that burns itself into your brain, and the memories of the people and the places are still there fresh and real and present. One of the problems was that there was too much that I wanted to put in, had to cut a lot out.

Yemen is not a country covered much in literature so what can you tell us about Yemen and a country and its people?

Yemen is a lost place, a country and a people still only hanging on to the very edge of the present. It’s almost as if the magnetic pull of the past is continually drawing them back. Traditions, religion, harsh and inaccessible country, fiercely independent heavily armed tribes, the unremitting dry – all these things pull them back in time, and make Yemen the place it is. I’ve never seen a more harshly beautiful place, but a lot of what you see makes you want to cry.

The subject of your novel is very current – but you portray both sides of the argument of the terrorists and the oil company – what do you hope people will take away from your novel?

I hope people will enjoy the story and the language, get a kick out of spending a bit of time in Yemen, go along for the ride – there’s a lot of action. I’ve tried to concentrate on that and not let the themes overwhelm. The themes are there, but as an undercurrent, I hope. Money, oil, power, greed, betrayal, trust, faith – these are the main themes. When faced with a situation that is clearly wrong, how far would you be willing to go to do the right thing? And what is the right thing, in this modern world, when you are in the middle of an ancient place where the rules are very different? In my writing I’m trying to blend science and literature, action and ethics, make it as real as I can.

We love the way you’ve woven the Arabic language and the numerals into the book. Do you speak Arabic yourself? Which languages do you speak and does that help with your writing?

French is my mother tongue. That’s what I grew up speaking, reading and writing. I even learned my science and math in French. I also studied Russian and Latin when I was a kid at school, and later, Spanish. I still have trouble sometimes when speaking English: I know the French word I want to use, but can’t find the English one. I worked in the Middle East for a long time, and worked pretty hard for a while at learning Arabic. It wasn’t much of a success. I know enough to make people there smile. My Turkish is better (it’s a much simpler language). Knowing other languages, and, for instance, being able to read Maupassant in the original French, I think makes you a better writer.

Your backstory is just as impressive if not more so than Claymore’s. What has been a highlight or a memorable moment from your own work?

The chance to live in many different places, go there not as a tourist but working with the local people and having the time to let the places really get into you so you can feel them, so that they stay with you, has been great. I’ve been very lucky. Early in my career, still in my twenties, I started an engineering consulting firm with four partners. We spent the best part of 20 years building it up to a thousand-person enterprise, sold it in 2006. Working for ourselves allowed the freedom to go after the kind of work we wanted to do in the paces that interested us. I was young and did things you can’t and would not do now. A few highlights: spending time with Yuruk Kurdish nomads on the Turkish-Iraqi border, eating with them, learning their language, falling in love (for a very short time – it was always going to be impossible, and dangerous); finally finding the woman who by some miracle was made for me and eloping with her to Ghana in West Africa where I’d been working rehabilitating village water wells, and getting married in a village ceremony deep in the forest in a tiny village, our nuptials toasted by the village chief; crawling up the to the edge of a river at night in Ethiopia, drunk and the world spinning, and looking out across into Eritrean rebel held territory as the Mengistu regime was falling, hearing the gunfire up and down the valley and the tracers looked so beautiful, like night rainbows.

Can you tell us anything about your next book and where it’s set?

Orenda books has just agreed to publish the sequel to ‘The Abrupt Physics of Dying’ – it’s called ‘The Evolution of Fear’. The first chapter of the sequel is included in the back of Abrupt Physics. It’s set partly in Istanbul (my favourite city in the whole world, where I’ve spent a lot of time), and in Cyprus, in the Med, where I lived and worked for about eight years. A fascinating place, with a history so deep and complex that once you get into it, feels like a maze with no exit. The conflict between Turkish-occupied North Cyprus and the Greek south is the backdrop. Evolution and extinction, life and death, renewal and loss are key themes.

Thanks very much Paul for meeting and having a chat. And for bringing that Hamour fresh from the Red Sea. I have quite honestly not tasted anything quite like this before. (We passed on the eyeballs funnily enough) Oh what a taste and what a book! Thank you for taking us to Yemen and for sharing your experiences and the history of the country. Quite a journey!

Booktrail Boarding Pass Information:

Twitter: @Hardisty_Paul

Website: – paulehardisty.wix.com