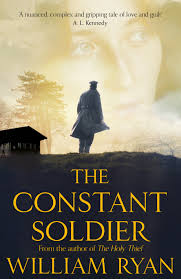

William Ryan -The Constant Soldier

Today’s the day when William Ryan, still riding high on his success with his latest novel The Constant Soldier, takes time out to head on over to the Booktrail for some a drink of something nice, a chat about books and an insight into the father – son relationship in the novel…THE CONSTANT SOLDIER

Have you read this astounding novel? If not,why not? You have to, it’s really good but it will make you cry. But fear not, I also plan to ask Mr Bill why on earth the novel doesn’t come with a box of tissues or a comforting hug or something..

Why did you want to tell this story? The rest of your novels are set in Russia aren’t they?

The novel is based on an album of photographs, many of which were taken at a rest hut for the SS officers and men who worked in Auschwitz. The photographs belonged to a man called Karl Hoecker, who was the adjutant to Richard Baer, the Commandant of Auschwitz from the middle of 1944 up until the Red Army arrived in January 1945, and it’s during this period that the photographs were taken. I saw some of them in a newspaper when they first came to light in 2007 (they were donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum by a former US army officer who found them in a bombed out Frankfurt apartment in 1945) and I was fascinated by how ordinary the men and women in the photographs appeared – and how relaxed, despite the fact that in some of the photographs every person pictured was executed for their part in the Holocaust.

I suppose I wondered what must have been going through their minds as, by June 1944, which is when the first of the photographs was taken, the Western Allies had landed in Normandy and the Soviets had won the war on the Eastern front, so they must have known that they would soon have to pay the penalty for their crimes. Initially, I think I thought the novel would be about the shift in power in the last few months of the war, but it turned into quite a different novel.

I didn’t entirely desert Soviet Russia though – I do have the woman driver of a T34 tank approaching from the east …

What do you think are the themes in the book? atonement? Love? the human spirit?

I think I wanted to explore what led the people in the photographs to do the things they did – because I think the terrifying thing is the many of them probably were ordinary people. I also wanted to think about what they must have felt when it was clear the war was lost. I suppose the novel is about the small steps ordinary people take that lead them to a place where they are committing great evil, and – yes – about the possibility of atonement.

I think Brandt, the central character, realises he has to do something to make up for his participation, however unwillingly, in the crimes of the Nazi regime. We’re probably never very far away from collective evil, even in our relatively stable democracies, so it’s also about people’s personal responsibility to stand up against evil. When we hear some of the things that a US presidential candidate is saying about making members of a particular religion carry identifying documents and how millions of Mexicans are going to be forcibly repatriated – and receives considerable support – then that worries me.

Brandt is an interesting character. What made you want to write from his point of view?

I think I needed a character who had been part of the terrible things that happened wherever Nazi Germany achieved power, but at the same time stand apart. He understands, to an extent, the mentality of the SS from the camp because he has fought on the Eastern Front – so he is more than aware of the Nazi regime’s cruelty. But he regrets his participation and he sees the presence of the women prisoners who work at the rest hut as an opportunity to atone, in a small way, for the evil committed in his name. I didn’t only write from his point of view – I also write from Agneta, the woman prisoner who he knew before the war, and Neumann, an SS man and then Polya, a woman tank driver in the approaching Soviet army. They’re all different parts of the picture – but you’re right to say that Brandt is the one who carries the story.

Brandt really fascinated me. Can you tell us more about him?

When the Nazis annexed Austria in 1938 Brandt, as an idealistic young student, decided to resist in a small way by distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. When he was arrested, he was given a choice – a concentration camp or the army. He chose the army and by the time we meet him again, in 1944 Brandt has been damaged – both physically and mentally – by his decision. So when he finds Agneta, who he inadvertently caused to be arrested in Vienna, working at an SS rest hut that has been built near his home, it seems obvious to him that he has to try and help her, as well as the other women prisoners.

The problem, of course, is that any direct action he takes will place his own family at risk – so he has to bide his time. I suppose the novel is driven by his determination to do a good thing – in defiance at the terrible evil that surrounds him – but how he has to balance his obligations. It’s not always easy doing the right thing – and the question, for much of the novel, is whether he’ll succeed.

The father/son relationship is very special. It made me cry. What are you hoping people take from the novel?

It’s funny, I was a bit concerned the father-son relationship was under-written but it turns out to be an element of the novel that a lot of early readers have found very moving. I wish I could say it was carefully thought out but it sort of developed on its own – just from asking how would a father and son react in such a situation? Each feel a responsibility towards the other and a desire to protect the other – but the circumstances in which they find themselves make that responsibility and protectiveness an almost impossible burden for both of them. And when Brandt begins working for the SS, for honourable reasons that he can’t reveal to his father, then the relationship comes under even greater strain. How they muddle through and continue to love each other is, I suppose, something that people relate to. And maybe all father-son relationships are underwritten in a way …

What kind of research did you do and how? (especially for Nazi Germany and the menace in the hut)

I read a great deal and I spent a lot of time looking at photographs, which I do for all of my novels. We have very few sources from the point of view of the perpetrators of the Holocaust but Gitta Sereny’s Into that Darkness and Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men – Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland were two very important sources. The more I read about Nazi Germany, and the Holocaust, the more inexplicable it seems – just profound, yet banal, evil of it.

Why don’t you provide hankies with the book?

Oh dear. I seem to have made a lot of people cry with this book. But good tears, I think. Worthwhile, I hope.

With many thanks to William Ryan for stopping by. And for providing me with several boxes of hankies for his next books.

Booktrail Boarding Pass Information: The Constant Soldier

Author/ Guide: William Ryan Destination: Auschwitz Departure Time: WW2

Twitter: @/WilliamRyan_ Facebook: /william.ryan Web: william-ryan.com