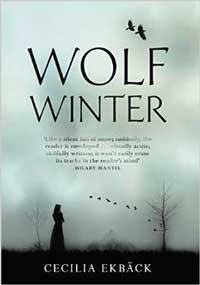

Sweden – CECILIA EKBACK – There’s something on that mountain…

There were only six homesteads on Blackåsen Mountain so finding the one where I was going to be meeting Cecilia Ekbäck to talk about her novel Wolf Winter should not be that difficult. Getting here had been though, what with the snow that seemed to envelop everything, even mu thoughts. But the husky dogs took me part of the way and then my Swedish snow books took over as I trudged up the mountain, past the Kings Throne, over Goat’s Pass and right to Cecilia’s door

I approach the nicest looking homestead there – and Cecilia is there ready to greet me. We go quickly inside where a log fire is burning and she gives me a blanket to wrap around me. Then comes the cake –

I approach the nicest looking homestead there – and Cecilia is there ready to greet me. We go quickly inside where a log fire is burning and she gives me a blanket to wrap around me. Then comes the cake –

And then the questions I have for Cecilia –

You were born in Northern Sweden, Swedish is your first language and your parents come from Lapland. How much did this influence the setting of your book and your ability to recreate it on the page?

Massively! I think my childhood is in this story in the shape of the setting, the culture and drivers such as the Church. The stories of my parents and grandparents are in there. The fear we felt growing up is in there. The characters are spun from people in my past. The plot is all imagined.

Swedish Lapland in the 18th century – you paint a picture of hardship and suspicions of witchcraft. Did you research old Swedish folklore for the book? (any stories in particular?)

A lot of the folklore is still there. I researched – read everything I could find, but the most valuable information I got from the interviews with my grandmother and her friends. And I remembered stories from my childhood. We grew up with tales about sprites and fairies, like the ones about ‘the boy on the bog’ who would steal your things if you had bad thoughts…— or Santa Claus who was not a large, jovial man dressed in red but a small, grey goblin who lived in the barn and who would punish you if you did not treat him right.

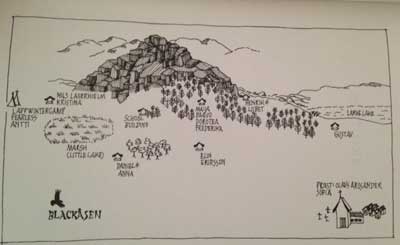

Is Blackåsen Mountain based on a real place in particular? Where in Lapland do you envisage the mountain and the landscape?

Blackåsen Mountain doesn’t exist as a physical place, but its nature is something I remember from my childhood: a combination of the places and memories I have from Hudiksvall, where I grew up, Knaften and Vormsele, the two small villages in Lapland where my grandparents lived, and Sånfjället, a mountain close to the Norwegian border, where our family had a cabin. Blackåsen is the embodiment of what I felt like growing up in the north of Sweden. It represents the fear, the doubts, the religious fervour, the loneliness and the need to fit in and to belong.

I imagine the mountain to be 70 kilometres inland of Luleå town – as I state in the very loose sequel I am writing right now and where maps are an important part of the tale.

Tell us more about the existence of the homesteads

As part of its nation-building in Lapland in the early 17th century, Sweden encouraged colonialisation and a lot of land that had previously been used by the indigenous people, the Sami, (referred to as ‘Lapps’ throughout Wolf Winter, as that was the name used at the time) was distributed to new settlers. Today a ‘homestead’ is more about the ownership of forest rather than houses. These estates are inherited, and it can be a hugely emotional issue in families – who gets to take them over.

Setting is vital to your story. How important do you think setting is in fiction in general? How did you go about recreating Swedish Lapland on the page?

My grandmother used to say, ‘I don’t think I’m living in Lapland as much as Lapland is living in me.’ And growing up in northern Sweden, its setting has made its mark. The long winters, the six months darkness, and the seemingly endless forest landscape – contrasted with the summer midnight sun, the hot weather and the absolute explosion of flora and fauna; one season is lived as quietly as the other is, exuberantly. This, our setting, governs, to a large part, the rhythm of our lives and imprints itself on our psyches. I am not certain I had to recreate it on the page, as much as just ‘let it flow,’ if you see what I mean?

Perhaps because of how powerfully we are marked by it, place—in the broadest sense of the word—has taken on a big role in Scandinavian crime writing and contributes to its uniqueness. The location where the scene is laid—the architect of the experience in the mind of the reader—is more than simply a supporting element in much of our fiction. I believe that this is why Scandinavian crime writing has such a broad appeal, blurring the line between highbrow and lowbrow forms of literature

In WOLF WINTER, I wanted ‘place’ – the mountain – to be almost a character in its own right. It felt right to give it a voice in the interludes. Blackåsen Mountain watches the settlers. It doesn’t care. It is dispassionate. It has already seen many of them come and go and it will see many more come and go after them. I brought this ‘place’ down onto the characters and let it impact them to the full.

In WOLF WINTER, I wanted ‘place’ – the mountain – to be almost a character in its own right. It felt right to give it a voice in the interludes. Blackåsen Mountain watches the settlers. It doesn’t care. It is dispassionate. It has already seen many of them come and go and it will see many more come and go after them. I brought this ‘place’ down onto the characters and let it impact them to the full.

As for setting in fiction in general, I think it is always important. Setting impacts characters, their drivers and mood.

The role of the church and the priest in the community was fascinating to learn about. Where did you learn of this?

Again, I read whatever I could find – history books, local books, such as Om Tider som Svunnit [About Times Past – author’s translation of title], by Wolmar Söderholm, 1973, produced locally in the town of Lycksele to celebrate its 300th anniversary.

I wanted one of the characters to have direct links to what was going on in a broad national context and the priest Olaus Arosander is thus someone who has been close to the king. Olaus would have been very influential in his local community. Priests taught, preached, punished, conducted national registrations (from 1686 priests were required to conduct yearly catechetical hearings and keep records of births, marriages and deaths in church books) and also played a vital propaganda role. They had to explain the necessity of the wars to their parishioners and draw links between the parishioners’ sins and poor war performance, and vice versa. The wars would later come to have another consequence for the church. Pietist tendencies were reinforced by Swedish soldiers who returned after having been prisoners-of-war in Russia with a more personal kind of faith, enjoying meeting at home, leading each other in worship and Bible study. In response, the Konvetikelplakatet, a law forbidding ’unofficial’ religious gatherings was passed, with fierce punishments for those who dared to defy it.

The character of Maija who is Finnish is a tough and fearless woman. Do you think she embodies the qualities you would have needed to survive in such an environment?

In so many ways, yes. Maija has a number of traits from the women in my family – stubbornness, strength, wisdom – qualities indeed needed to survive in a harsh world. But she is also flawed, human. She wants well, she is passionate, but proud and so much remains unsaid. I resonate with her – as a mother, as a daughter and as a woman.

With thanks to Cecilia for braving the cold on the mountain to talk to me today. And I will never forget my visit to Blackåsen Mountain- her grandmother was right when she said -‘I don’t think I’m living in Lapland as much as Lapland is living in me.’ That’s how the book affects you.

Booktrail Boarding Pass Information:

Twitter:@ceciliaekback

Facebook:karinceciliaekback

Website: www.ceciliaekback.com